This is the third of three essays.

Summer ’22 Essay 1

Summer ’22 Essay 2

Why So Sad? Encourage Self-help and Other Support Strategies

“People underestimate their own therapeutic powers…The most powerful buffer in times of stress and distress is our social connectedness…” —Bruce Perry

Key Concept: Being “well regulated”, being “dysregulated”, what that means & what we can do about it

October 1990.

My dad gives me the Beastie Boys album Paul’s Boutique for my 13th birthday. He passes it to me over the edge of his hospital bed.

“I’ll take you fishing this summer, John,” he promises.

A few weeks later he’s back in hospital after descending into alcoholism to the point of no return.

Before he dies, he leads me to the bathroom by the ICU. He shows me the clotted blood passing through him.

He tells me, “Do as I say, not as I do.”

Not long after, he’s gone.

June 2022.

We are clever apes. Working as a team, we can turn an overwhelming crisis into a manageable challenge. We can turn a frustrating problem into a fascinating puzzle. This is why we are all still here. All eight billion of us. Because of our clever, cooperative, ape brains.

Our amazing brains have allowed us to thrive on this planet, but at the same time they operate within limits. It’s arguable that they are not optimized for the modern world we have constructed. We have developed the tools of the modern information age much faster than our brains can adapt by evolution. One of the outcomes of that is an increased chance of going a little over the emotional handlebars. To say the least.

In describing the levels through which our emotional states move, Dr Bruce Perry will use the words “regulated”, or “dysregulated”. For me, understanding how this happens and learning to recognize those different states that our brains can get into has been game changing. A key point, how well we can think depends on the state our brain is in —which in-turn depends on all the inputs we’re getting via our senses. This is known as “State Dependent Functioning” 1

Growing up, through my teenage years, I recall entering these prolonged odd states of feeling outside of my body or like I was caught in a weird time-loop or something. It was something that, years later, I now understand psychologists call “dissociation”.

To sound fancy, I had become neurologically dysregulated. But why? What was causing it?

Thinking about it now, considering what I’ve learned from reading Hari, Heckler, and Perry/Winfrey, I believe one trigger for me getting into these states, was a sense of being different from my peers.2

The feeling of difference was in comparison to my peers at school—and even among my skate friends outside of school. The fact was I did not know anyone else, beyond my sister, whose dad had died3. I remember that thought flashing into my head a lot. The resulting feeling was aloneness. Not loneliness. Aloneness.

We’ve talked about how that sense of being cut off from the group is a fundamental existential threat. It follows that a sense of disconnection from your crew could very well trigger that cocktail of neurochemicals that gets us hopped up into that state of fight, flight, freeze etc.

When we feel dissociation what we are perceiving is that change in brain state driven by some stress-inducing factor. Like being different from our group and potentially unable to be fully accepted and therefore guaranteed protection.

In scenarios like this, without us realizing, our brains naturally remove their resources from the neocortex and deploy more heavily into the pre-language, act-now-think-later, areas of the mid and lower brain. Dr Perry has shown this to be the case. He has also shown how and why we can manage that response and get ourselves back to a calm, rational state of being. A state of being more suited to making well-reasoned decisions. What we call being “well regulated”.

One of the most important parts to all of this is learning to notice when we are dysregulated. 4 Sometimes that’s easy. Anxiety is a strong feeling we can place in the fear-related category. Hard to define exactly but also hard to miss when we’re in the thick of it. The tricky thing with anxiety however is that feeling of fear manifests but with no clear threat in sight. Anxiety is an amorphous shroud. A dreadful internal fog. Figuring out where our brain is getting the threat-signal from is the subtle secret door to find if we are to locate the root of what happened to us. And for me, from growing up in a house with a terminal alcoholic, there’s plenty to be mindful of.

I’ve always tried to remind myself that the feelings are temporary and if we can identify the stressor and take some steps to address it then we can start to get back to baseline. But consciously identifying the stressor is what’s called top-down regulation, thinking our way through it. This is what cognitive behavioral therapy is all about. There is also a bottom-up approach we can add to our toolkit.

The brain is the central processing unit that drives the complex physical system of our bodies. Given that physicality, the other big part of dysregulation can be managed with physical actions that address the very brainstem itself. This we call bottom-up regulation because it’s about starting at the brainstem, at the bottom of the brain where the signals from our five senses first arrive from the world around us. With that, long-story-short, when those signals and thoughts get us all out of whack, what Dr Perry reminds us of is that patterned, rhythmic, repetitive motions have a profound calming effect.

When our brains are first developing—literally in utero—they make the first of many associations that will build up to become our automatic response system. Our fight-flight survival mode. One of the earliest and most powerful associations that gets imprinted is between rhythmic sound and motion and the feeling of being safe. In the womb we are for the most part comfortable and receiving nutrients while sensing the rhythm of our mother’s heartbeat and perhaps feeling the gentle bounce as she walks.

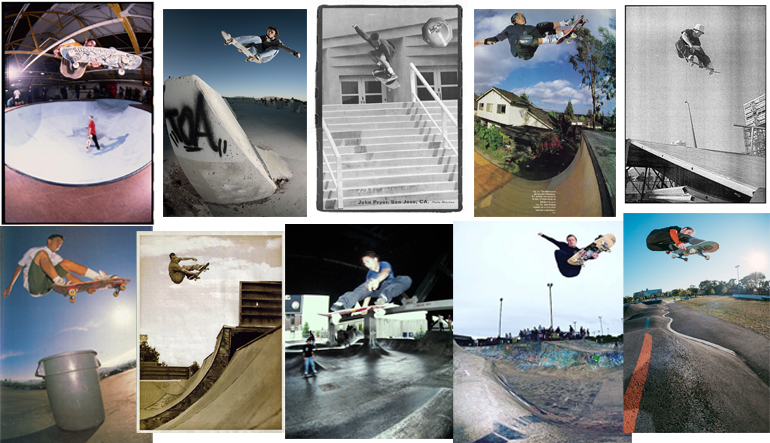

This is why if you are upset then skating down the street focused on staying balanced while the click, click, click of your wheels on the pavement vibrates up through the soles of your feet; sitting and quietly zeroing your focus in on playing a simple chord progression on your acoustic guitar; going for a walk, run or a bike ride; this is why those things help. Patterned, rhythmic activity helps regulate a dysregulated brain from the bottom up by connecting it back into its original safe place. Which in-turn allows your brain to relax and re-open access to the top rational, time-experiencing, planning, thinking part of your brain. It’s only at this point, once we are reasonably regulated that—in small doses—we can begin to think through the traumas that have made us who we are, and take intentional, conscious, steps to forgive ourselves, connect with loved ones, and continue together through this ongoing healing process called life.

Footnotes:

- You can see a 20-minute lecture by Dr Perry explaining State Dependent Functioning here

- If you have a couple of hours, you can find his full lecture series here

- I’m self-analyzing—one day I’ll talk to a professional about this but for now you’re all I’ve got so if you can bear with me, I really appreciate it. Hopefully we both get some value out of it.

- On top of that, to die from alcoholism then, and probably still now, has a stigma and shame about it. I will argue that stigma and shame is not based on sound logic reasoning. Alcoholism is a symptom of an underlying emotional challenge. I believe it to be an unconscious mechanism we fall prey to because it helps us cope with the pain of what happened to us. Alcoholism is not something we do to ourselves; it is something that happens to us.

- Problems in this world abound I believe because a lot of us are wandering through life way more stressed than we are aware of, therefore in a suboptimal state when it comes to good decision making. Taking our own life or lives of others are decisions made under extreme emotional duress, they are not based on solid logic, far from it, and they can’t be because the stressed brain is rendered incapable as it fluxes into a fight-flight survival mode.

- Increase the ingredients for stress and then couple that with easy access to the means to do harm and you have a perfect storm recipe for disaster. Malcolm Gladwell lays this out well in his book, Talking to Strangers in the chapter titled Sylvia Plath.

- Why So Sad Fundraising Pack 4 can be found here